| VINTAGE VIRGINIA |

Conquering a mountain with muscles and mules

In the "Breaks" of the Big Sandy River, deep within the awesome gorge known as the Grand Canyon of the South and unseen be motorists zipping by on a modern highway over-head, stands an unlikely memorial.

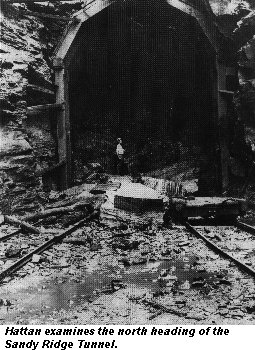

The 1.5-mile Sandy Ridge tunnel, 10th longest in the United States, even by today's standards is considered one of the greatest engineering achievements of the century. Yet few have heard the story behind the tunnel or the stretch of railroad of which it is a part, a transportation link carved with muscle, laid with bare hands and lined with the unmarked graves of those who died trying to see it through.

For many years, ambitions industrialists from the Northeast had cast long, lustful eyes on the rich coalfields of Southwest Virginia and Eastern Kentucky. As early as 1831, the need for a thoroughfare from the regions of the South to the Midwest and North was recognized, but economics and red tape delayed the project.

A shortlived construction attempt began in 1886, but ceased when the company providing financial backing went broke. It wasn't until 1902 that George L. Carter purchased the road and work began anew. The Blue Ridge section of the railroad was completed in 1908, and in 1912, the Clinchfield Railroad decided to complete its 35-mile branch, consisting of 20 tunnels and eight bridges.

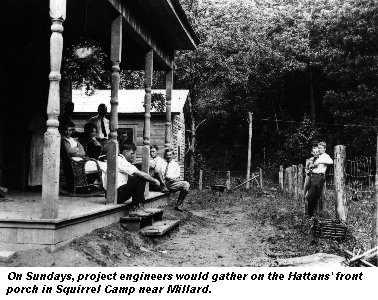

William Cary Hattan, a Rockbridge County native, was hired to oversee the project as Division Engineer, a task not unsuited to him, since he already had assisted on the Blue Ridge portion, overseen constuction of18 tunnels in 14 miles of track.

But that did not entirely prepare him for some of the hardships he encountered on the new project. Passages from his journals read like stories of the old West, tales of brawls and rivalry, of the crew that fought and worked and drank its way to win the battle against time through the Breaks Canyon.

The difficulties began immediately.

Hattan arrived in Dante on May 21, 1912, ready to begin setting up camps

in nearby Millard only to find he could not reach the area except on horseback.

He and another engineer went back to Johnson City, Tenn., for supplies,

then set out to find a team of horses.

Finally, Hattan made an arrangement with John Kerr, a Millard farmer,

to use his team to bring supplies into the area and to set up camp

on his property until they could prepare the engineers' camps.

Hattan also arranged to board with the Kerrs,

bringing along his bride of two months.

Finally, Hattan made an arrangement with John Kerr, a Millard farmer,

to use his team to bring supplies into the area and to set up camp

on his property until they could prepare the engineers' camps.

Hattan also arranged to board with the Kerrs,

bringing along his bride of two months.

John Kerr, his wife Fanny and three small children lived in a house typical of the area: no running water, no electricity, not even the convenience of an outhouse.

Throughout the summer, Sara Hattan helped the Kerrs and cared for the children while the engineers hastily constructed houses in the camps, and by mid-August the lodging was ready, although faciliities remained primitive. Staples had to be brought by the Kerrs or by mule and wagon from Dante. Food consisted of hogs and chickens raised at the camps, and occasionally wild game or fish -- even roosters. Dr. Rufus L. Phipps rode on horseback to tend the sick and injured.

The construction years were the most turbulent the area had known. With a mixture of Italian, German, Russian, Negro and local workers crowded together in tar-paper shacks or tents reeking of garlic, perspiration and corn whiskey, tempers often were short. Contractors had to employ interpreters who spent more time settling disputes than lining up work. Meager pay was spent on liquor or gambling and there were many fights and killings.

One day, after a drunken holiday spree, a group of Italian laborers complained about the meal the cook prepared. The dragged him out of his tent, gave him a mock trial and hung him.

Many of the workers had no roots or families in this country, so when they were killed in the tunnels or the camps, they were buried along the tracks in unmarked graves.

They worked with the most primitive equipment. The steam shovel, whose parts broke down dialy, delayed work consistently. The moutnain was literally blown out with dynamite, and the rocks were moved with carts and mules. There were no modern bulldozers to dig away the foundations, only the pickaxe, shovel and muscle. It took a mule team half a day to go eight miles.

On June 4, 1913, construction finally began on the Sandy Ridge Tunnel. The Perkins brothers, W.B. and E.J., contractors for Rinehart and Dennis of Charlottesville, began to dig, one at the north and one at the south end.

Every day brought some new kind of trouble. One of the most dangerous problems was dust and smoke from the blasting. Sometimes it became so bad work had to be stopped completely.

There were numerous accidents from dynamite exploding prematurely. Breakdown of equipment was the norm and heavy storms and high water, snow and freezing temperatures in the winter plagued the workers constantly. One worker was killed by a high voltage wire falling on him. Days later, two were killed when a blasting switch was thrown before they got out of the way. Sometimes the accidents claimed five or 10 workers at a time.

But the great day finally arrived. At 6:30 a.m. on May 20, 1914, the tunnel was "holed": both teams met in the center. When a check was completed, it was learned the line measurement was off by less than one inch. A little more than eight months later, the track was connected between the Elkhorn Extnsion and the Clinchfield Railroad, and a special train, carrying all the railroad officials, stood by as George Carter drove the last spike completing the route that took 84 years to bring from conception to final delivery.

Today, the Sandy Ridge tunnel is familiar only to railroad crews hauling loads of coal, but the legend of its construction lives around every bend.